What actions can mitigate the impacts of land fractionation on the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community?

Doran Dalton, Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community

Background

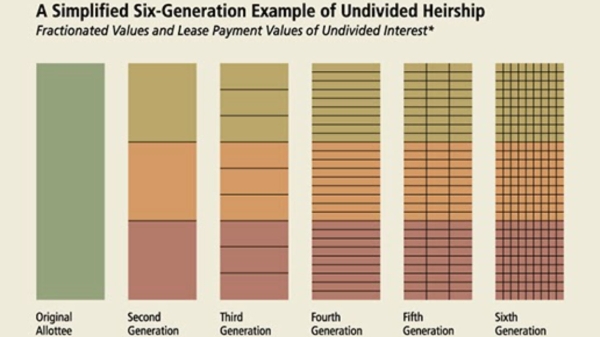

Through the General Allotment Act of 1887, also known as the Dawes Act, the concept of landownership was introduced to Native American tribes. The act subdivided tribal lands into individual plots, giving a pre-determined amount of land acreage usually to the male head of household of individual families. The purpose of the General Allotment Act was aimed at solving the "Indian Problem" by assimilating Native Americans into mainstream United States society. The act ended up replacing many of the communal land traditions that many Native tribes hold with a culture centered not on the community as a whole, but rather on the individual.

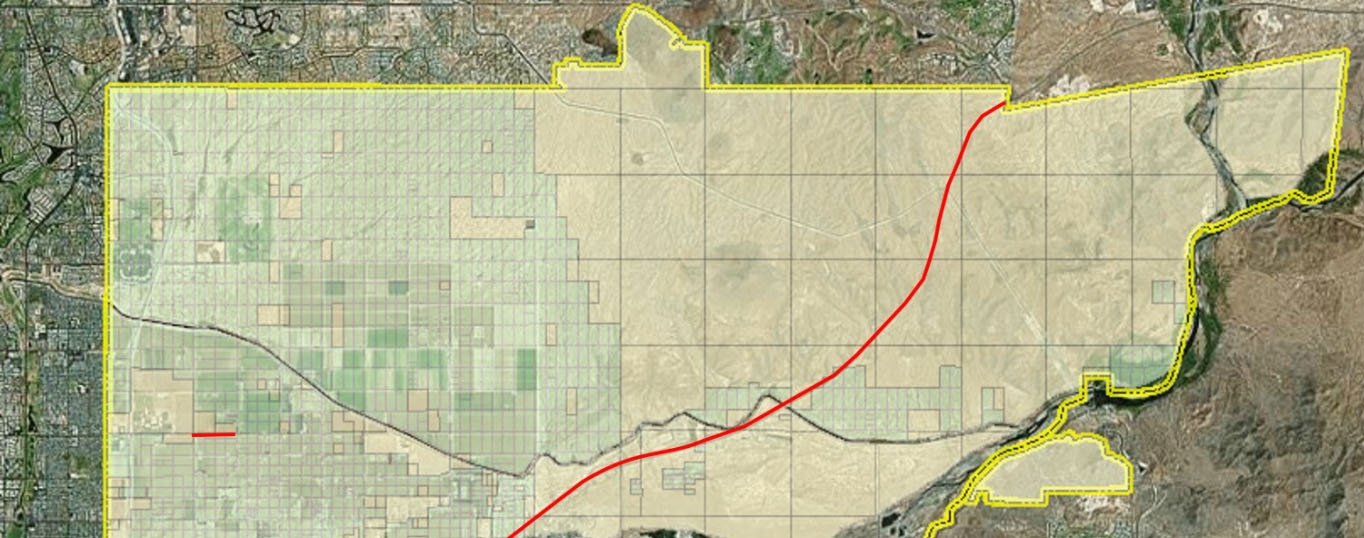

On the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community (SRPMIC), there were 947 original land allottees. In the Salt River District, each head of household was granted a 30-acre parcel. In the Lehi District of the community, each head of household was granted a 5-acre parcel.

One hundred and eight years after the Dawes Act created allotments, 43% of those allotments are "landlocked" without legal ingress or egress or utilities, due to generational land fractionation. In some cases, ownership interests are so small — like the size of a Post-It note — that nothing can be done with them individually.

Research questions

-

What are some ways that tribal departments can advance existing processes internally to try to help mitigate the fractionation of allotted lands?

-

How can tribal departments and tribal leadership grow awareness about the fractionation issue with landowners?

-

How can tribal departments and tribal leadership promote and encourage the creation of wills and future land planning, such as creating family subdivisions?

Methods and findings

Dalton initially started this project with the intention of creating, changing or advancing some of the internal processes that tribal departments use or can use to help mitigate the issues of land fractionation. Working with three of the tribal departments who work with landowners on land issues, the processes that these departments use were examined, and different ways to improve those processes were discussed. As the project progressed, a litany of other issues were brought to light. In some cases, land owners are not necessarily members of the SRPMIC tribe, which can complicate matters. One of the ways that the tribe uses to gain access to landlocked areas is to pay surrounding landowners a lease fee in order to gain legal access. Paying for rights-of-way for access and utilities can come with a pretty heavy price tag. The process to do a land appraisal can get expensive, and on top of that, compensating the landowners can also be very costly. Some of these issues can be solved by doing land swaps with the landowners who are not enrolled in the tribe. Landowners can also choose to waive compensation while granting the allottees legal access to their land shares. These mitigating factors, however, are out of the direct control of the tribe and its departments, and they rely solely on the individual landowners to decide to make those choices.

For these reasons, Dalton shifted his focus to educating landowners about the choices available to them in order to avoid further fractionating their land. Some of those choices include working with the Legal Services Department to create wills for landowners and creating future land planning. Creating a will allows the landowner to designate exactly what they want to have done with their land after they pass. They can choose to leave the land to a single person or to have a Joint Tenancy with the right of Survivorship among several individuals. Land planning could mean they create a family subdivision that enables the land to be divided up into different lots, thus eliminating the decision of what to do with the land or how to divide it up after that person is gone.

The tribe is also looking at other ways that its members can move back onto the reservation by planning apartment buildings and looking at other ways to provide housing.

Partners

Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community

-

Community Development Department

-

Engineering and Construction Services Department

-

Legal Services Department

Impact

Members of the SRPMIC have a generational and historic tie to the land, traditions, culture and people that make up this great tribe. Many members of the community are unable to build or place a home on the reservation due to the impacts that land fractionation has had on the accessibility of land for ingress/egress and utilities that are needed in order for them to live on the reservation. Through education and awareness of this issues, landowners can take some mitigating measures into their own hands, which could help their families to have a home on the reservation.

Deliverables

Dalton created an educational Story Book Map to provide landowners, tribal employees and leadership with a basic level of understanding of how land ownership in the community is set up. He also provided educational materials to tribal leaders who can inform their constituents about the fractionation problem as well as carry some of those ideas to policymakers on the federal level.

Doran Dalton

GIS Specialist

Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community

Community Fellow, 2021

My name is Doran Dalton. I am a Native American, belonging to the Hopi and Pima tribes in Arizona, and I am an enrolled member of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community (SRPMIC). I currently work for the SRPMIC as a Geographic Information Systems Specialist. I also live on the SRPMIC with my wife and our two dogs. I love doing anything outdoors, except yardwork, and also just love spending time with friends and family.